“A strategic approach to address the digital divide in the handicraft sector”

Overview

With their skills and traditional knowledge, there are 6.8 million Indian artisans, who have been large suppliers of unique handicrafts to the global market. The handicraft industry contributes US$ 3.39 billion to handicraft exports.However, these noteworthy statistics do not translate to promising results as these exports currently account for a paltry 4-5% of the global market share (Handicraft Census, 2011). With the ever-changing world scenario, this sector has seen the introduction of new designs, products and remarkable innovations at global level, indicating the need for institutional support to Indian artisans in order to catch up with the changing needs.

There exists a dearth of data backed literature to ably demonstrate the key challenges faced by the artisans’ community, particularly their ability and willingness to adopt technology-led interventions. While historically, the handicraft sector has held great importance, today, the lack of comprehensive data on artisans coupled with challenges in terms of design upgradation, product innovation, seamless delivery of products and access to digital markets, reflects the need to strengthen the individual artisan capabilities by leveraging digital technology solutions significantly.

The consideration of digital readiness and willingness is central to designing tech-based products and services. Building upon the same, this study by CATALYST AIC aimed at understanding the key challenges the Indian artisanal communities face in their effort to increase production and enhance the quality of products for a global market. Our sample comprised 874 artisans from 22 districts across Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. Methods of convenience sampling were followed where the sample has been derived from resources provided by Catalyst AIC partner organizations working with artisans at the grass-root level in these states.

Sample characteristics

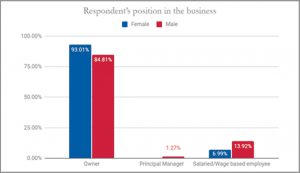

The sample had 75% of respondents as women. This good representation of women was owing to their substantive presence in the rural handicrafts sector, especially when it comes to organizations working at grassroots level.

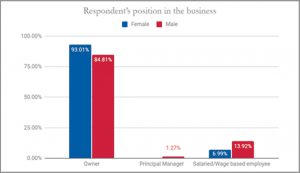

85% of the respondents were business owners of their enterprise and free to sell their products/do business with whoever they want, while 15% were salaried/wage workers at various

Handicraft census , Office of Development Commissioner. (2011). Handicraft Census 2011. http://handicrafts.nic.in/Page.aspx?MID=BOII5FUynjpl5RZJJ8nW1g==

In Rajasthan, most of the artisans came from Bikaner, Jaipur, Kota, Sikar and Udaipur while Uttar Pradesh was represented by Mahoba, Banda and Bareilly.

Insights from the study

Currently, there exists no data-repository or survey which informs about the digital readiness of artisan community in India, with our survey being first of its kind where we comprehensively measure these aspects of business operations among artisans.

To map the existing digital landscape for enabling tech-based solutions, the qualifiers are categorized broadly, but not limited to, into the following parameters:

- Nature of employment and Business Activity amongst the artisan community

- Local Ecosystem Digital Ability

- Digital Literacy

- Ability and desire to onboard an online marketplace

- Ability to learn and navigate different digital platforms

- Business operations (obtaining orders, raw material procurement, client communication and delivery of their products)

- Documentation

- Access to Credit and Financial Management

- Failure in Function points

- Women’s agency and decision making power in financial decisions

Nature of employment and Business Activity amongst the artisan community

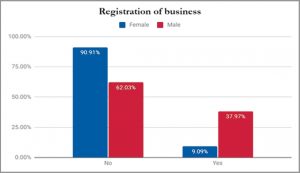

The survey results reflected that more than half of the respondents did not have registration for their businesses. Despite 58% of the artisans operating for a decade, 77% of the businesses were not registered. Lack of registration barred the artisans from being a part of formal supply chain and financial setups.

The respondents who had registration for their business, stated Artisan Card as the most prominent form of registration, followed by MSME Udyog Aadhar. However, the field visits have confirmed that artisan card was not a reliable registration mechanism and many non-artisans have also been allotted the card. Alongside, it was noted that there has been little or no government assistance to help artisans avail benefits through the card.

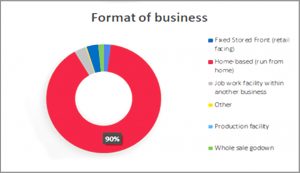

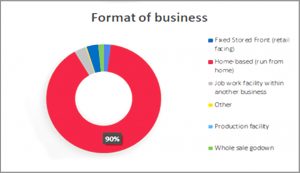

In terms of format of the business, 89.49% of the respondents had a home-based setup.

- Home based artisans were the largest category of artisans in terms of their ways to organize themselves as a business unit. However, home based businesses were the least likely to have government-based registrations. 81% of home based business setups reported no registration (refer chart 3).

- Women-run businesses had the majority of their set ups as home-based businesses (80%) as opposed to the ones owned by men, which was only 19% .The reason likely to be that home-based businesses allows women to get some earnings without stepping out of the vicinity of their homes, often a constraint due to restrictive gender norms. A study by LEAD at Krea University on Women home-based businesses professed that this narrative largely plays out as women also bear a disproportionate burden of unpaid household work.

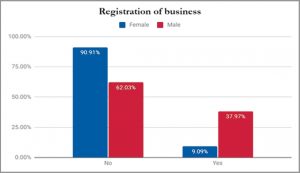

- In terms of registration, again we see a stark divide as 90.91% of businesses run by women entrepreneurs were not registered, as compared to 62% of businesses run by men. The lack of registration by women artisans results in a major lag in adopting digital marketplace opportunities in the day-to-day business processes. (refer chart 4)

Local Ecosystem Digital Ability

- Ownership and access to Smart-phones

Smart-phones have been considered for the analysis as it plays an integral role in driving the ability to adopt digital platforms.

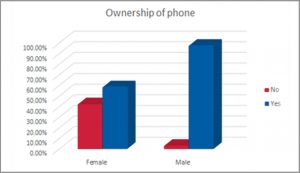

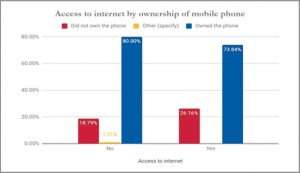

- In terms of ownership, 68% of the artisans said that they own the mobile phone which they were using. Out of these 68% who owned a mobile phone, half of the respondents said they have a smartphone.

- Amongst the remaining 32% respondents who did not have ownership of the mobile phones, the artisans shared a phone with their family members. There were also cases where they shared their phones with neighbors (9%).

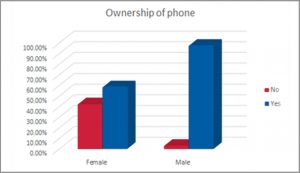

- onsidering the digital divide, the survey also entailed the analysis of disproportionate smart phone access available to women. Out of those who owned a smartphone, 96% of the men owned the phone but this number almost drops to half in the case of women artisans (47%), (refer chart 5).

Our survey points out to the practice that artisans (especially women) access a mobile phone and its internet features through intra-household sharing of mobile phones.

Ecosystem players are recommended to develop ‘multiple accounts feature’ on their digital platforms that are marketed for these artisans. Studies conducted by Dalberg with IWWAGE and LEAD at KREA University also suggested this as a part of their design principles for women users based on the fact that UI features should allow for ease of discovery of content relevant for women who may not be primary users of the phone. This feature of enabling the opening of multiple accounts on the same mobile phone would be extremely relevant in order to bring all artisans in one family into the fold of the digital ecosystem.

- Connectivity challenges and internet accessibility

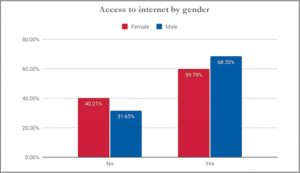

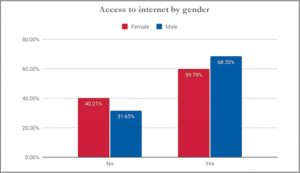

96% of respondents had access to a stable source of electricity connection while 94% of our sample had satisfactory phone network connectivity.Expanding on the infrastructural barriers, the survey pointed out that 58% of the artisans had access to the internet.

- The insights gathered from the survey reflected that 50% of the artisans had simple feature phones which don’t use any internet.

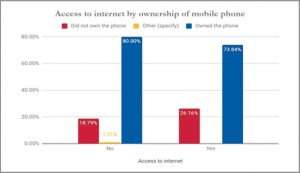

- Those who could access the internet, more than 96% of artisans connected to the internet through personal data packs that require constant top-ups while only 1% of the artisans used a stable Wi-Fi connection to access the internet. A mere presence of intermittent connectivity is never a propelling factor for any digital solution, unless designed otherwise, using suitable technologies.

The ecosystem players are recommended to develop applications taking into consideration the low-bandwidth, speed asymmetry and high latency (period between requesting information and beginning to receive it) in the geographical region the artisans are located. The mobile and web based applications shall leverage newer technologies:

- To make the application less data intensive (alternate formats of images etc) as Wi-Fi access is low.

- To allow bi-directional data flow even in case of poor internet connectivity (for instance, caching mechanism).

c) API designed to have a pared-down version of the application optimized for low bandwidths and for simple keypad phones.

3) Banking ecosystem

98% of the respondents reported to have a bank account, with only 68% having their bank accounts linked with their phone number. The fact which needs special attention is that barely 54% of them were using their bank accounts for business purposes.

Digital Literacy

- Smartphone application knowledge

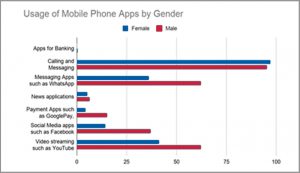

While almost all the respondents from our sample knew how to make calls and use messaging (SMS) applications on their phones, more than half of the artisans responded that they took help from the family members to operate phone based applications.

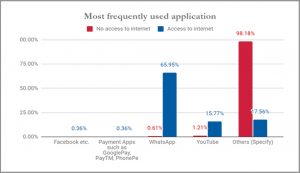

Examining the usage pattern, almost 50% of the artisans were using applications like YouTube and WhatsApp. Among the users of these applications, 82% of them knew how to upload and send photos from these platforms.

Overall, 46.4% of our respondents knew about video-based content and were able to find and access this content. 20% of the sample was comfortable with using social media platforms.

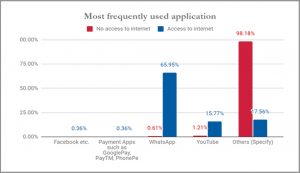

To gain a deeper understanding of the frequency of usage of these digital applications, we see that amongst those who had access to the internet, as low as 0.36% of the artisans used payment apps frequently and a mere 15.77% used YouTube frequently.(refer chart 7)

Digital Payment knowledge

It can be noted that as the complexity of the applications increases, we see a drop in the usage. While only 1/3rd of the respondents had an email account, a mere 7% of the artisans were using and accepting payments through digital payment applications.

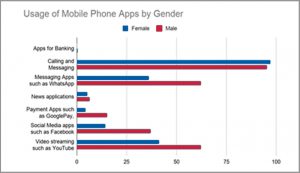

Gender Lens: Analyzing mobile applications knowledge through a gender lens, men were more familiar with applications like WhatsApp (62.33%) compared to women (36.23%) (refer chart 8). This lower usage can be attributed to the fact that in the case of smartphone, more than half of the women get access through shared ownership where the concern for privacy constrains their desire to use such messaging platforms.

In several cases, it is highlighted that the children of the artisans send the messages on WhatsApp to the potential buyers or relatives to negotiate a sale, or post pictures on social media platforms and on e-marketplaces and, most importantly, they help the artisans with digital payments.

Ability and desire to onboard an online marketplace

Our study results noted that 98% of the artisans never made a sale online (digital platform, e-commerce websites, and Facebook or WhatsApp groups).

Amongst the artisans who have sold their products online, half of them have used Amazon or Flipkart. Interestingly, artisans have also sold their products on WhatsApp and Facebook groups.

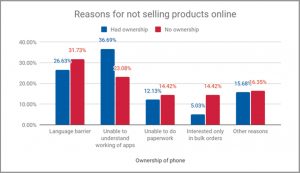

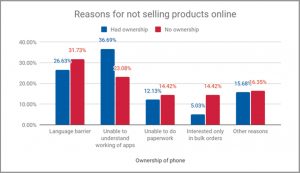

Amongst the artisans who have never made a sale online, most cited 28% referenced their inability to comprehend the protocols laid down by the online platform (this includes asking the artisans to detail and list all their products, materials used, design name and price), 22.3% mentioned their inability to understand and comprehend English which hindered their participation in online platforms (as most platforms are in English and not in their local language), and 13% stated that they were unable to understand the paperwork and registration requirements for the platform to recognize them as sellers.

From amongst those who had ownership of the phone, the most cited reason for not being able to sell their product online entailed the lack of understanding of online applications. (refer chart 9)

Interestingly, 66% of the artisan agreed that digital management solutions which help them in making accounts or inventory management would help grow their business. In order to onboard those to an online platform, the artisans suggested that they would need assistance in all aspects such as clicking, uploading photos, understanding the features of an app and also for getting their paperwork done.

Only 16% of the artisans reported that they had been either contacted or provided training to sell products online. However, among the people who have previously received any training to sell online, only 0.06% artisans were able to navigate the applications with operational ease.

Ability to learn and navigate different digital platforms

The survey results captured a very critical operational hurdle faced by the artisan community.

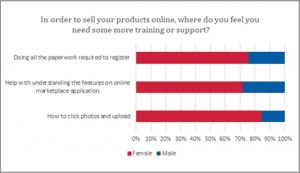

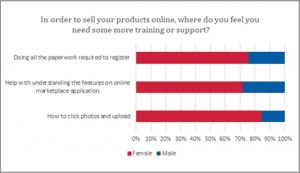

- 57% of the respondents stated that they need to be taught how to click and upload photos

- 60% stated that they needed help navigating through the various features of the platform, and

- 40% of them stated that they needed assistance to file the paperwork necessary to register them on the platform itself.

Furthermore, it’s interesting to note that a higher percentage of women asked for assistance in clicking and uploading photos while the case was reversed when it came to assistance in operating the application – Men requested for more operational assistance, compared to women. This can arise from the fact that more women considered clicking and uploading as a first major hurdle to sell products online.

Considering the digital platforms for leveraging upskilling and training for the artisan community, an overwhelming 92% of the respondents expressed a desire to learn designs through online videos or live classes. Through the field visits, we learned that the artisan lacked the capacity to innovate new designs and thus were dependent on major exporters to manufacture products which would be easily bought in the market. The artisans were open to the idea of online design training with the desirable mode being live classes as it would provide flexibility of asking queries and clearing doubts. The respondents who did not wish to use these digital mediums, the prominent reasons have been a restriction of time at home or their inability to understand or use the digital medium.

In order to enhance the digital readiness among the artisans, the ecosystem players (Development community, Artisan collectives and Communities) need to provide multiple targeted interventions in order to scale their businesses:

- In addition to providing phones and means for digital communication to the artisan community, the digital applications can be curated as per the artisan community vernacular/regional language option, basically keeping it multilingual and UX which is easily identifiable.

- The design of digital platforms can be made women-centric and should include possibilities of knowledge sharing so that women can use their existing networks to explore new features of the application.

- Considering the importance of the children and their role in facilitating digital transactions for their parents (the artisans), future endeavors by ecosystem players can also include training the children (adolescents in particular), along with training programs for the artisans, as a part of hand holding.

- There can be more provisions of building Point of sale infrastructures to inculcate trust factor in the artisan community towards digital presence and overcome perception barriers.

- The prerequisites to register themselves on the phone based applications can be made simpler by eliminating the requirement of a lot of paperwork or avoiding an email account ownership as a primary requirement.

- The desirability of the artisan community to adopt digital management solutions can be translated into adoption of digital solutions by hand-holding in terms of training on navigating different digital platforms and to be able to carry out basic requirements like clicking and uploading pictures. The access to live training or a physical design center where they can be taught new designs and methods to replicate these, can be a relevant service.

Business operations

Orders were mostly physically obtained with the customer visiting their facility (91%).

Customers often made phone calls to these artisans (53%) as well to place their order and then some orders were also obtained by visiting Craft Melas.

Craft Melas have been reported as an important source for obtaining orders. Almost half the respondents visited these melas 2-4 times a year and 77% of them have reported that attending craft mela has been a profitable business opportunity.

From our field visits, it can be interpreted that with respect to online marketplaces, there should be a facility by which the artisans are able to convince the potential buyers about the quality and materials used for their crafts and the bulk buyers can see a sample of the product as well. The development of the brand for the online sale was found pertinent to building an element of trust with the buyers; hence the startups can focus on building enhanced visual experience platforms to bring standardization.

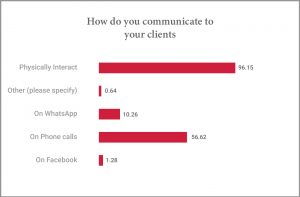

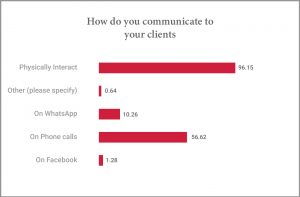

Our study recorded that most of the post order interaction happened in the form of physical interaction. However, 60% of the artisans said they remained in touch with their buyers on phone through calls. (refer chart 11)

The artisans who used their mobile phones during the process of obtaining orders or carried out post-order communications via phone, WhatsApp has been found to be the most used communication platform after phone calls.

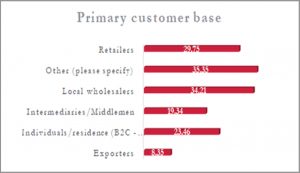

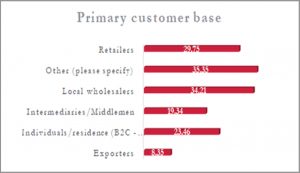

Only 25% of the artisans were able to sell their products to the final customer. Rest of them was either selling it to an institutional buyer or some kind of middleman. Additionally, 70% of them sold the products from a home-based facility and were only able to sell in local neighborhoods.

The potential startups can provide scalable solutions by digitization of the supply chain for the last mile entrepreneurs and by upskilling the artisans on awareness around best practices to follow when it comes to selling their products online. The ecosystem players can adopt the model of procuring the products directly from the artisans or from the nearby collection center.

- The model can entail a solution to the artisans’ reluctance to bear the logistical cost to supply products far-away and being accustomed to selling products locally even if it takes a hit on the margin. There can be digital solutions for inventory management and connecting artisans directly to the retailers.

- Order needs to be made physically first and instances where advance is also provided; further communication can then be done through phone calls and messages.

- Additionally, Craft Melas as an opportunity should be leveraged because this helps to showcase the products physically after which large orders can be placed remotely.

Documentation

Our study highlighted that while only half of the artisans maintained books of accounts, only 1.5% of them maintained their accounts digitally. 94% of them maintained it in a Khatabook or paper.

Out of these 50% who maintained any accounts, only 26% of them kept accounts for internal transactions. 30% of the artisans provided bills on purchase of products and out of these, only half of them provided a formal bill.

While respondents agreed that digital accounting would help their business and can work as a reference for formal lending, they would require a lot of handholding to onboard to any digital platform.

The startups can provide digital platforms for recording sales, purchase and other transactions, which can be used as a reference for obtaining formal credits by the artisans.

Access to Credit and Financial Management

88% of the respondents stated that they have a GST account. Out of the remaining respondents, only 25% of them have tried applying for a GST account.

- Working Capital Requirements – 95% of the artisans had not taken credit for working capital requirements. Out of the small percentage of respondents who availed working capital requirements, the major source had been the family/relatives and after that, cooperatives/SHGs. The methods to cover the initial costs included advance provided by buyers in terms of money or raw material, as the major source.

- Insurance – Majority of the respondents (98%) had never taken insurance for their products. The lack of knowledge of such services was cited as the prominent reason for not buying insurance.

- Credit source – Our survey concluded that a scant proportion of the respondents had taken credit from a formal source (3%). The most prominent reasons for this include process-delays and the formal sources not offering small recurring loans.

In case of sudden loss, 83% of the respondents drew from their personal savings.

The economic players can tap on the opportunity to provide digital infrastructure to provide a digital footprint of transactions which can be used by artisans for larger loans and enhance peer-to-peer lending. They can use business models which provide advance capital, keeping in mind that the business is largely dominated by the advance payment models.

There can also be verticals encompassing various insurance services tailored to the needs of artisans, along with organizing knowledge management sessions on this topic for the artisans.

Parallel to the capital requirements, there can be accelerations from the startups to lay the framework for i) providing formal credits- which has the facility of providing recurring small loans ii) guide the artisans in expediting the processes involved in obtaining formal credits.

Drawing focus on the sudden loss faced by the artisans, the startups can envision a system which takes into account the risk associated with small loans.

Additionally, it is pertinent to focus on getting the mobile linkage done so that artisans can be assured of timely payments.

Failure in Function points.

Our survey identified certain functionalities around loan disbursal and subsequent collateral requirements which trigger disproportionate access in terms of gender.

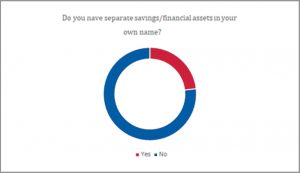

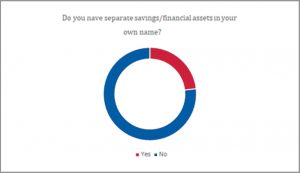

In case of credit access by women, traditional institutions required the loans to be co-signed by a male relative/husband and required separate collaterals in the name of the women prior to disbursing loans. This practice acts as a constraint especially when 77% of our women respondents claimed that they did not have assets separate from their spouse/family. This was supported by the findings that women were half as likely as men to access formal loans (8.25% in case of men against 4.44% for women).

Women’s agency and decision making power in financial decisions

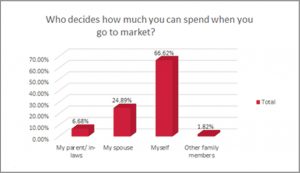

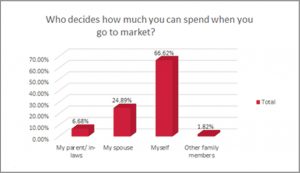

During our survey, women mentioned that the decision on day-to-day expenses was made by them. However, when it comes to financial security, barely 23% of the women reported that they have separate financial assets in their name. 75% of our women respondents mentioned that the women should have a right to sell and buy in the market without husband’s permission.

Empowerment in terms of utilizing the savings as per their discretion, saw a major setback as, even though in 50% of the cases, decisions regarding how much to save in the household were either taken by the woman herself or are jointly taken along with the spouse, 65% of the women respondents stated that they used these savings for household expenditure.

A very small proportion of women respondents (4%) expressed interest in using their income to acquire more land, 10% stated that they wanted to use it to repay old debts and 11% stated that they wanted to use it to expand on their current business activities. It is a reflection of the patriarchal setup where women view their artisanal work as supplementary income hence they do not see relevance in targeting capital to grow their business. Additionally, women largely directing their income towards household activity share its origin from the lack of financial literacy amongst women.

Tapping on the positive approach of women’s interest in having the intra-household bargaining power, building financial products with use cases for women, can be the focus. Additionally, the digital platforms or applications can be designed with information presented simply and with photos or illustrations which are easier to understand.

Besides replicating a credit system, the ecosystem players can consider making the women artisan’s work visible by integrating it with the marketplace, given that women were largely involved in home-based setup and had movement constraints in accessing the market.

In order to drop the narrative of women artisan’s work as an extension of their household work, the startups can conduct knowledge sessions keeping –expansion of business through reinvestments as the prime focus. Innovations in integrated financial products tailored to women’s financial needs can help in the trade-off women artisans are forced to undertake, for instance, the decision to invest in child’s education while foregoing business expansion.

Conclusion

A disruptive shift towards digital technology worldwide is now a necessity to sustain a business ecosystem and the Indian handicraft sector needs to adopt the various digital solutions to overcome the hurdles they face. The artisans can harness the opportunities to gain access to a larger audience through digital marketplaces and financial platforms, resonating with the insight that almost all the artisans in our sample showed enthusiasm towards adopting digital platforms. While access to electricity and phone network connectivity showed positive signs, the staggering low penetration of smartphones (more in case of women artisans) is the reason for almost negligible usage of key digital applications.

The survey points towards the fact that a mere ownership of the mobile phone or access to internet did not translate to higher usage of digital applications by the artisans. The barrier in accessing the digital marketplace is twofold. Firstly, the complexity of the online platforms pertaining to navigating various features coupled with the inability of the artisans to comprehend the English language and understand registration protocols, devoid them from participating in a digital ecosystem. Assisted first time use and handholding, in terms of training on using the digital platforms and additionally, designing the applications which is user-friendly in terms of language and interface, is pertinent to any digital setup for the artisan community. An enhanced visual experience for online display where potential bulk buyers can see a sample of the product themselves which has been well branded, is a basic requirement alongside digitized supply chain. Secondly, with almost 90% of the artisans having a home-based setup and overall 77% businesses not registered, restricts their ability to access any state-sponsored assistance. It is imperative to conduct awareness and literacy campaigns to enroll all the artisans in the government registration programmes.

What acts as an accelerator in the establishment of digital solutions is the desirability of the women (90%) to upskill themselves by digital means, considering that our sample has 75% women as respondents. Moreover, almost 50% of the artisans were using applications like YouTube and WhatsApp. The artisan community requires a push to build on their digital literacy and set up basic operational frameworks like maintaining digital documentation to access credits and other assistance. While almost all of the artisans owned a bank account, only 54% of them are currently using their bank accounts for business purposes. Hence, the next step will require building awareness around the benefit of online sales and marketing by enabling them the experience of interaction with customers with the expansion of the customer base through digital payment methods.

Our study highlights the disproportionate access faced by women in case of financial credits, smartphone, registration of businesses and many more. The ecosystem players (inclusive of policymakers, digital application creators, leaders of the artisan community, mobile network operators, formal lending institutions and the development community), can focus on building financial products with use cases for women, to make them part of the digitally-enabled business ecosystem.